একসময় মনে করা হতো এডটেক বা শিক্ষাপ্রযুক্তি বুঝি কেবল মহামারিকালীন এক সাময়িক সমাধান বা ‘কনভিনিয়েন্স’। কিন্তু সেই ধারণা এখন আমূল...

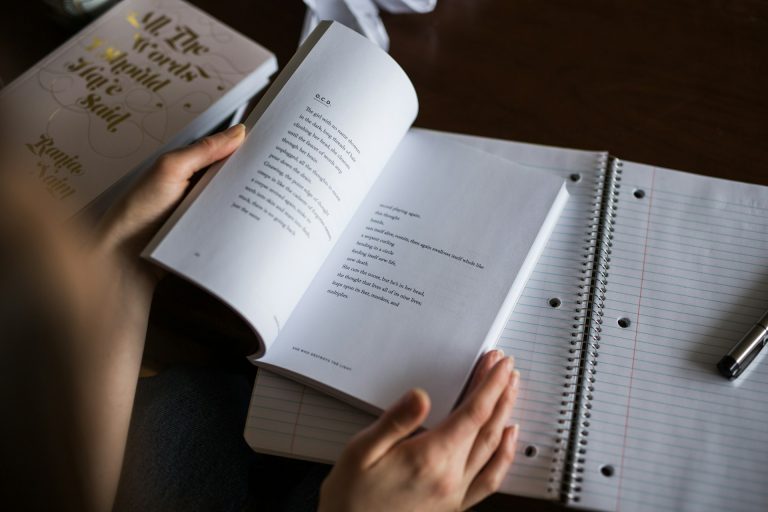

আন্তর্জাতিক সাহিত্যের দৃশ্যপটে সম্প্রতি এক উল্লেখযোগ্য ঘটনা ঘটে গেল। কবিতার বিশ্বজনীন যাত্রায় নতুন মাত্রা যোগ করতে যুক্তরাষ্ট্রের ঐতিহ্যবাহী প্রতিষ্ঠান 'একাডেমি...

শিক্ষা খাতে কৃত্রিম বুদ্ধিমত্তা বা এআই-এর সংযোজন এখন আর কেবল নতুন কোনো টুল বা গ্যাজেট কেনার মধ্যে সীমাবদ্ধ নেই। বিষয়টি...

ঢালিউড অভিনেত্রী বিদ্যা সিনহা মিমের ব্যস্ততা এখন তুঙ্গে, পরিস্থিতি এমন পর্যায়ে পৌঁছেছে যে চিত্রনাট্য বা গল্প তৈরি হওয়ার আগেই নির্মাতারা...

কৃত্রিম বুদ্ধিমত্তা বা আর্টিফিশিয়াল ইন্টেলিজেন্স (এআই) এখন আর কল্পবিজ্ঞানের বিষয় নয়, বরং এটি আমাদের দৈনন্দিন জীবনের এক অবিচ্ছেদ্য অংশে পরিণত...

বিশ্বব্যাপী মানুষের মধ্যে স্বাস্থ্যসচেতনতা বৃদ্ধির সঙ্গে সঙ্গে খাদ্যাভ্যাসেও বড় ধরনের পরিবর্তন লক্ষ্য করা যাচ্ছে। বিশেষ করে পুষ্টিকর ও ভেষজ গুণসম্পন্ন...

ক্রিকেট বিশ্বের নজর এখন অস্ট্রেলিয়ার মাটিতে চলমান টি-টোয়েন্টি বিশ্বকাপের দিকে, যেখানে অ্যাডিলেইড ওভাল প্রস্তুত হচ্ছে ভারত ও বাংলাদেশের মধ্যকার হাই-ভোল্টেজ...

আমেরিকানরা যখন তাদের জীবনে কৃত্রিম বুদ্ধিমত্তার (এআই) প্রভাবের সাথে খাপ খাইয়ে নিচ্ছে, তখনও এটি নিয়ে উল্লেখযোগ্য পরিমাণে অবিশ্বাস রয়ে গেছে।...

গ্রুপ সেরা হয়ে নকআউট পর্বে যেতে জয়ের কোনো বিকল্প ছিল না পিএসজির সামনে। ইতালির তুরিনে ইউভেন্তুসের কড়া চ্যালেঞ্জ সামলে তারা...

ইউএস ওপেনের ফাইনালে রোমাঞ্চকর এক লড়াইয়ের পর টেনিস বিশ্বের দুই শীর্ষ তারকা কার্লোস আলকারাজ এবং ইয়ানিক সিনার এবার এশিয়ান সুইংয়ে...